(Opinionated) answers to frequently asked questions on (green) open access, from a computer science (software engineering) research perspective.

Disclaimer: IANAL, so if you want to know things for sure you’ll have to study the references provided. Use at your own risk.

Green open access is trickier than I thought, so I might have made mistakes. Corrections are welcome, just as additional questions for this FAQ. Thanks!

Green Open Access Questions

- What is Green Open Access?

- What is a pre-print?

- What is a post-print?

- What is a publisher’s version?

- Do publishers allow Green Open Access?

- Under what conditions is Green Open Access permitted?

- What is Yellow Open Access?

- What is Gold Open Access?

- What is Hybrid Open Access?

- What are the Self-Archiving policies of common computer science venues?

- Is Green Open Access compulsory?

- Should I share my pre-print under a Creative Commons license?

- Can I use Green Open Access to comply with Plan S?

- What is a good place for self-archiving?

- Can I use PeerJ Preprints for Self-Archiving?

- Can I use ResearchGate or Academia.edu for Self-Archiving?

- Which version(s) should I self-archive?

- What does Gold Open Access add to Green Open Access?

- Will Green Open Access hurt commercial publishers?

- What is the greenest publisher in computer science?

- Should I use ACM Authorizer for Self-Archiving?

- As a conference organizer, can I mandate Green Open Access?

- What does Green Open Access cost?

- Should I adopt Green Open Access?

- Where can I learn more about Green Open Access?

What is Green Open Access?

In Green Open Access you as an author archive a version of your paper yourself, and make it publicly available. This can be at your personal home page, at the institutional repository of your employer (such as the one from TU Delft), or at an e-print server such as arXiv.

The word “archive” indicates that the paper will remain available forever.

What is a pre-print?

A pre-print is a version of a paper that is entirely prepared by the authors.

Since no publisher has been involved in any way in the preparation of such a pre-print, it feels right that the authors can deposit such pre-prints where ever they want to. Before submission, the authors, or their employers such as universities, hold the copyright to the paper, and hence can publish the paper in on line repositories.

Following the definition of SHERPA‘s RoMEO project, pre-prints refer to the version before peer-review organized by a publisher.

What is a post-print?

Following the RoMEO definitions, a post-print is a final draft as prepared by the authors themselves after reviewing. Thus, feedback from the reviewers has typically been included.

Here a publisher may have had some light involvement, for example by selecting the reviewers, making a reviewing system available, or by offering a formatting template / style sheet. The post-print, however, is author-prepared, so copy-editing and final markup by the publisher has not been done.

A (Plan S) synonym for postprint is “Author-Accepted Manuscript”, sometimes abbreviated as AAM.

What is a publisher’s version?

While pre- and post-prints are author-prepared, the final publisher’s version is created by the publisher.

The publishers involvement may vary from very little (camera ready version entirely created by authors) up to substantial (proof reading, new markup, copy editing, etc.).

Publishers typically make their versions available after a transfer of copyright, from the authors to the publisher. And with the copyright owned by the publisher, it is the publisher who determines not only where the publisher’s version can be made available, but also where the original author-prepared pre- or post-prints can be made available.

A (Plan S) synonym is “Version of Record”, sometimes abbreviated as VoR.

Do publishers allow Green Open Access?

Self-archiving of non-published material that you own the copyright to is always allowed.

Whether self-archiving of a paper that has been accepted by a publisher for publication is allowed depends on that publisher. You have transferred your copyright, so it is up to the publisher to decide who else can publish it as well.

Different publishers have different policies, and these policies may in turn differ per journal. Furthermore, the policies may vary over time.

The SHERPA project does a great job in keeping track of the open access status of many journals. You’ll need to check the status of your journal, and if it is green you can self-archive your paper (usually under certain publisher-specific conditions).

In the RoMEO definition, green open access means that authors can self-archive both pre-prints and post-prints.

Under what conditions is Green Open Access permitted?

Since the publisher holds copyright on your published paper, it can (and usually does) impose constraints on the self-archived versions. You should always check the specific constraints for your journal or publisher, for example via the RoMEO journal list.

The following conditions are fairly common:

- You generally can self-archive pre- and post-prints only, but not the publisher version.

-

In the meta-data of the self-archived version you need to add a reference to the final version (for example through its DOI).

-

In the meta-data of the self-archived version you need to include a statement of the current ownership of the copyright, sometimes through specific sentences that must be copy-pasted.

-

The repository in which you self-archive should be non-commercial. Thus, arXiv and institutional repositories are usually permitted, but commercial ones like PeerJ Preprints, Academia.edu or ResearchGate are not.

-

Some commercial publishers impose an embargo on post-prints. For example Elsevier permits sharing the post-print version on an institutional repository only after 12-24 months (depending on the journal).

Usually meeting the demands of a single publisher is relatively easy to do. Given points 2 and 3, it typically involves creating a dedicated pdf with a footnote on the first page with the required extra information.

However, every publisher has its own rules. If you publish your papers in a range of different venues (which is what good researchers do), you’ll have to know many different rules if you want to do green open access in the correct way.

What is Yellow Open Access?

Some publishers (such as Wiley) allow self-archiving of pre-prints only, and not of post-prints. This is referred to as yellow open access in RoMEO. Yellow is more restrictive than green.

As an author, I find yellow open access frustrating, as it forbids me to make the version of my paper that was improved thanks to the reviewers available via open access.

As a reviewer, I feel yellow open access wastes my effort: I tried to help authors by giving useful feedback, and the publisher forbids my improvements to be reflected in the open access version.

What is Gold Open Access?

Gold Open Access refers to journals (or conference proceedings) that are completely accessible to the public without requiring paid subscriptions.

Often, gold implies green, for example when a publisher such as PeerJ, PLOS ONE or LIPIcs adopts a Creative Commons license — which allows anyone, including the authors, to share a copy under the condition of proper attribution.

The funding model for open access is usually not based on subscriptions, but on Article Processing Charges, i.e., a payment by the authors for each article they publish (varying between $70 (LIPIcs) up to $1500 (PLOS ONE) per paper).

What is Hybrid Open Access?

Hybrid open access refers to a restricted (subscription-funded) journal that permits authors to pay extra to make their own paper available as open access.

This practice is also referred to as double dipping: The publisher catches revenues from both subscriptions and author processing charges.

University libraries and funding agencies do not like hybrid access, since they feel they have to pay twice, both for the authors and the readers.

Green open access is better than hybrid open access, simply because it achieves the same (an article is available) yet at lower costs.

What are the Self-Archiving policies of common computer science venues?

For your and my convenience, here is the green status of some publishers that are common in software engineering (check links for most up to date information):

- ACM: Green, e.g., TOSEM, see also the ACM author rights. For ACM conferences, often the author-prepared camera-ready version includes a DOI already, making it easy to adhere to ACM’s meta-data requirements. Note that some ACM conference are gold open access, for example the ones published in the Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages.

- IEEE: Green, e.g., TSE. The IEEE has a policy that the IEEE makes a version available that meets all IEEE meta-data requirements, and that authors can use for self-archiving. See also their self-archiving FAQ.

- Springer: Green, e.g., EMSE, SoSyM, LNCS. Pre-print on arXiv, post-print on personal page immediately and in repository in some cases immediately and in others after a 12 month embargo period.

- Elsevier: Mostly green, e.g., JSS, IST. Pre-print allowed; post-print with CC BY-NC-ND license on personal page immediately and in institutional repository after 12-48 month embargo period. To circumvent the embargo you can publish the pre-print on arxiv, update it with the post-print (which is permitted), and update the license to CC BY-NC-ND as required by Elsevier, after which anyone (including you) can share the postprint on any non-commercial platform.

- Wiley: Mostly yellow, i.e., only pre-prints can be immediately shared, and post-prints (even on personal pages) only after 12 month embargo. E.g. JSEP.

Luckily, there are also some golden open access publishers (which typically permit self-archiving as well should you still want that):

- PeerJ Computer Science: Gold (creative commons) and green.

- Usenix: Gold since 2008. Published with PeerJ. Authors retain their copyright.

- LIPIcs-based proceedings: Conferences publishing their papers via Dagstuhl’s Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics LIPIcs, such as ECOOP, FSCD, …

- IEEE Access: The ‘mega-journal’ from IEEE covering all IEEE’s fields of interest.

- PLOS ONE: The successful (nonprofit) mega-journal that also publishes computer science papers.

- Many venues in Artificial Intelligence, including AAAI, the Journal of Machine Learning Research, Computational Linguistics, the Semantic Web Journal, or the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS).

- Specialized conferences or journals such as the Journal of Object Technology or Computational Linguistics.

Is Green Open Access compulsory?

Funding agencies (NWO, EU, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, …) as well as universities (TU Delft, University of California, UCL, ETH Zurich, Imperial College, …) are increasingly demanding that all publications resulting from their projects or employees are available in open access.

My own university TU Delft insists, like many others, on green open access:

As of 1 May 2016 the so-called Green Road to Open Access publishing is mandatory for all (co)authors at TU Delft. The (co)author must publish the final accepted author’s version of a peer-reviewed article with the required metadata in the TU Delft Institutional Repository.

This makes sense: The TU Delft wants to have copies of all the papers that its employees produce, and make sure that the TU Delft stakeholders, i.e. the Dutch citizens, can access all results. Note that TU Delft insists on post-prints that include reviewer-induced modifications.

The Dutch national science foundation NWO has a preference for gold open access, but accepts green open access if that’s impossible (“Encourage Gold, require immediate Green“).

Should I share my pre-print under a Creative Commons license?

You should only do this if you are certain that the publisher’s conditions on self-archiving pre-prints are compatible with a Creative Commons license. If that is the case, you probably are dealing with a golden open access publisher anyway.

Creative Commons licenses are very liberal, allowing anyone to re-distribute (copy) the licensed work (under certain conditions, including proper attribution).

This effectively nullifies (some of) the rights that come with copyright. For that reason, publishers that insist on owning the full copyright to the papers they publish typically disallow self-archiving earlier versions with such a license.

For example, ACM Computing Surveys insists on a set statement indicating

… © ACM, YYYY. This is the author’s version of the work. It is posted here by permission of ACM for your personal use. Not for redistribution…

This “not for redistribution” is incompatible with Creative Commons, which is all about sharing.

Furthermore, a Creative Commons license is irrevocable. So once you picked it for your pre-print, you effectively made a choice for golden open access publishers only (some people might consider this desirable, but it seriously limits your options).

Therefore, my suggestion would be to keep the copyright yourself for as long as you can, giving you the freedom to switch to Creative Commons once you know who your publisher is.

Can I use Green Open Access to Comply with Plan S?

Yes, you can, but you are only compliant with Plan S if you share your postprint, with a Creative Commons License, immediately (no embargo).

But, unfortunately, the creative commons license is likely incompatible with the constraints of your publisher of the eventual paper. As a way around, in some (most) cases (e.g., ACM, IEEE journals, Springer) you are allowed to distribute your postprint with a CC BY license if you actually pay the hybrid open access fee. These fees are not refundable under Plan S, but this hybrid-and-then-self-archive route is compliant with Plan S.

What is a good place for self-archiving?

It depends on your needs.

Your employer may require that you use your institutional repository (such as the TU Delft Repository). This helps your employer to keep track of how many of its publications are available as open access. The higher this number, the stronger the position of your employer when negotiating open access deals with publishers. Institutional archiving still allows you to post a version elsewhere as well.

Subject repositories such as arXiv offer good visibility to your peers. In fields like physics using arXiv is very common, whereas in Computer Science this is less so. A good thing about arXiv is that it permits versioning, making it possible to submit a pre-print first, which can then later be extended with the post-print. You can use several licenses. If you intend publishing your paper, however, you should adopt arXiv’s Non-Exclusive Distribution license (which just allows arXiv to distribute the paper) instead of the more generous Creative Commons license — which would likely conflict with the copyright claims of the publisher of the refereed paper.

Your personal home page is a good place if you want to offer an overview of your own research. Home page URLs may not be very permanent though, so as an approach to self archiving it is not suitable. You can use it in addition to archiving in repositories, but not as a replacement.

Can I use PeerJ Preprints for Self-Archiving?

Probably not — and it’s also not what PeerJ Preprints are intended for.

PeerJ Preprints is a commercial eprint server requiring a Creative Commons license. It is intended to share drafts that have not yet been peer reviewed for formal publication.

It offers good visibility (a preprint on goto statements attracted 15,000 views), and a smooth user interface for posting comments and receiving feedback. Articles can not be removed once uploaded.

The PeerJ Preprint service is compatible with other golden open access publishers (such as PeerJ itself or Usenix).

The PeerJ Preprint service, however, is incompatible with most other publishers (such as ACM, IEEE, or Springer) because (1) the service is commercial; (2) the service requires Creative Commons as license; (3) preprints once posted cannot be removed.

So, if you want to abide with the rules, uploading a pre-print to PeerJ Preprints severely limits your subsequent publication options.

Can I use ResearchGate or Academia.edu for Self-Archiving?

No — unless you only work with liberal publishers with permissive licenses such as Creative Commons.

ResearchGate and Academia.edu are researcher social networks that also offer self-archiving features. As they are commercial repositories, most publishers will not allow sharing your paper on these networks.

The ResearchGate copyright pages provide useful information on this.

The Academia.edu copyright pages state the following:

Many journals will also allow an author to retain rights to all pre-publication drafts of his or her published work, which permits the author to post a pre-publication version of the work on Academia.edu. According to Sherpa, which tracks journal publishers’ approach to copyright, 90% of journals allow uploading of either the pre-print or the post-print of your paper.

This seems misleading to me: Most publishers explicitly dis-allow posting preprints to commercial repositories such as Academia.edu.

In both cases, the safer route is to use permitted places such as your home page or institutional repository for self-archiving, and only share links to your papers with ResearchGate or Academia.edu.

Which version(s) should I self-archive?

It depends.

Publishing a pre-print as soon as it is ready has several advantages:

- You can receive rapid feedback on a version that is available early.

-

You can extend your pre-print with an appendix, containing material (e.g., experimental data) that does not fit in a paper that you’d submit to a journal

-

It allows you to claim ownership of certain ideas before your competition.

-

You offer most value to society since you allow anyone to benefit as early as possible from your hard work

Nevertheless, publishing a post-print only can also make sense:

- You may want to keep some results or data secret from your competition until your paper is actually accepted for publication.

-

You may want to avoid confusion between different versions (pre-print versus post-print).

-

You may be scared to leave a trail of rejected versions submitted to different venues.

-

You may want to submit your pre-print to a venue adopting double blind reviewing, requiring you to remain anonymous as author. Publishing your pre-print during the reviewing phase would make it easy for reviewers to find your paper and connect your name to it.

For these reasons, and primarily to avoid confusion, I typically share just the post-print: The camera-ready version that I create and submit to the publisher is also the version that I self-archive as post-print.

What does Gold Open Access add to Green Open Access?

For open access, gold is better than green since:

- it removes the burden of making articles publicly available from the researcher to the publisher.

- it places a paper in a venue that is entirely open access. Thus, also other papers improving upon, or referring to your paper (published in the same journal) will be open access too.

- gold typically implies green, i.e., the license of the journal is similar to Creative Commons, allowing anyone, including the authors, to share a copy under the condition of proper attribution.

Will Green Open Access hurt commercial publishers?

Maybe. But most academic publishers already allow green open access, and they are doing just fine. So I would not worry about it.

What is the greenest publisher in computer science?

The greenest publisher should be the one imposing the least restrictions on self-archiving.

From that perspective, publishers who want to be the greenest should in fact want to be gold, making their papers available under a permissive Creative Commons license. An example is Usenix.

Among the non-golden publishers, the greenest are probably the non-commercial ones, such as IEEE and ACM: They require simple conditions that are usually easy to meet.

The ACM, “the world’s largest educational and scientific computing society”, claims to be among the “greenest” publishers. Based on their tolerant attitude towards self-archiving of post-prints this may be somewhat justified. Furthermore, their Authorizer mechanism permits setting up free access to the publisher’s version.

But greenest is gold. So I look forward to the day the ACM follows its little sister Usenix in a full embrace of golden open access.

Should I use ACM Authorizer for Self-Archiving?

The ACM offers the Authorizer mechanism to provide free access to the Publisher’s Version of a paper, which only works from one user-specified URL. For example, I can use it to create a dedicated link from my institutional paper page to the publisher’s version.

However, Authorizer links cannot be accessed from other pages, and there is no point in emailing or tweeting them. Since only one authorizer link can exist per paper, I cannot use an authorizer link for both my institutional repository, and for the repository of my funding agency.

These restrictions on Authorizer links make them unsuitable as a replacement for self-archiving (let alone as a replacement for golden open access).

As a conference organizer, can I mandate Green Open Access?

Green open access is self-archiving, giving the authors the permission to archive their own papers.

As a conference organizer working with a non open access (ACM, IEEE, Springer-Verlag) publisher, you are not allowed to archive and distribute all the papers of the conference yourself.

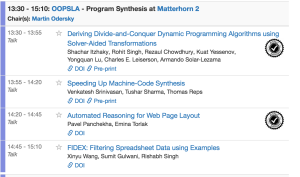

What several conferences do instead, though, is collecting links to pre- or post-prints. For example, the on line program of the recent OOPSLA 2016 conference has links to both the publisher’s version (through a DOI) and to an author-provided post-print.

For OOPSLA, 20 out of the 52 (38%) of the authors provided such a link to their paper, a number that is similar in other conferences adopting such preprint linking.

As a conference organizer, you can do your best to encourage authors to submit their pre-print links. Or you can use your influence in the steering committee to push the conference to switch to an open access publisher, such as LIPIcs or Usenix.

As an author, you can help by actually offering a link to your pre-print.

What does Green Open Access cost?

For authors, green open access typically costs no money. University repositories, arXiv, and PeerJ Preprints are all free to use.

It does cost (a bit of) effort though:

- You need to find out the specific conditions under which the publisher of your current paper permits self-archiving.

- You need to actually upload your paper to some repository, provide the correct meta-data, and meet the publisher’s constraints.

The fact that open access is free for authors does not mean that there are no costs involved. For example, the money to keep arXiv up and running comes from a series of sponsors, including TU Delft.

Should I adopt Green Open Access?

Yes.

Better availability of your papers will help you in several ways:

- Impact in Research: Other researchers can access your papers more easily, increasing the chances that they will build upon your results in their work;

- Impact in Practice: Practitioners may be interested in using your results: A pay-wall is an extra and undesirable impediment for such adoption;

- Improved Results: Increased usage of your results in either industry or academia will put your results to the real test, and will help you improve your results.

Besides that, (green) open access is a way of delivering to the tax payers what they paid for: Your research results.

Where can I learn more about Green Open Access?

Useful resources include:

- SHERPA / RoMEO: Green Open Access conditions and restrictions for all journals and publishers.

- The UCL Open Access FAQs.

- The IEEE Self-Archiving FAQ.

Version history:

- 6 November 2016: Version 0.1, Initial version, call for feedback.

- 14 November 2016: Version 0.2, update on commercial repositories.

- 18 November 2016: Version 0.3, update on ACM Authorizer.

- 20 November 2016: Version 0.4, added TOC, update on commercial repositories.

- 06 December 2016: Version 0.5, updated information on ACM and IEEE.

- 20 December 2016: Version 0.6, added info on Creative Commons and AI venues.

- 27 July 2018: Version 0.7, update on where to archive. Released as CC BY-SA 4.0.

- 18 November 2018: Version 0.8, updated info on Elsevier.

- 10 September, 2019: Version 0.9, added question on Plan S compliance.

Acknowledgments: I thank Moritz Beller (TU Delft) and Dirk Beyer (LMU Munich) for valuable feedback and corrections.

© Arie van Deursen, November 2016. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.